December sight is estimated at $600 million. With minor adjustments to prices and assortment qualities reported in categories.

Sightholders and brokers reported that 25 percent boxes were deferred or left on the table.

An India a sightholder said that they had already complained at the previous two De Beers sights that prices were too high to polish diamonds with a profit. We haven’t seen any movement from De Beers so there was other option but to leave the goods.

Diamantes said that prices at the ALROSA sale declined, and the negative sentiment at the sight reflected the mood in the rough market at large.

Rough trade on the open market was week, even though boxes were offered at a loss with generous credit terms.

A 89.23 ct D VVs1 pear shape diamond sold for $11 million at the New York Magnificent Jewels sale.

The total auction was $66.6 million and featured a selection of colourless and fancy coloured diamonds.

A pair of pear shaped fancy light yellow diamond earrings weighing 52.88 and 51.46 cts sold for $5.4 million, a 21.30 ct, oval cut fancy light pink Golconda diamond that sold for $4.25 million. And a 1.42 ct oval cut fancy red VS2 diamond sold for $2.16 million.

Phase one of the Panama Gem & Jewellery Centre is completed. Fourteen of the world’s largest diamond trading firms are taking up their allocated offices.

They are among 45 international companies with annual revenues of more than $13 billion, and employ 85,000 people globally. Are Kiran Gems, Diarough NV, Rosy Blue, Bhavani Gems, Interjewel, Jewelex, M. Suersh, the Niru Group, ILI Diamonds of the A. Rachminov Group, Atit Diamonds of the Shairu Gems, Dianco, Ofer Mizrahi Diamonds, S. Schnitzer Diamonds and S. SB Bichachi Diamonds Group.

The Panama Gem & Jewellery Centre is the region’s only recognized diamond exchange.

With a futuristic profile and metallic exterior, and covers 1,578 square meters. A high security perimeter includes a parking area for tenants and visitors, and landscaped gardens. The first level includes the headquarters of the PDE, including its administrative offices, meeting rooms and 300 square-meter trading floor.

Twelve Indian diamond companies including Kiran Gems, Asian Star and Rosy Blue India, have signed three year contracts with ALROSA at the World Diamond Conference,

Each of the companies signed separate contracts with ALROSA and will buy rough diamonds worth USD 2.1 billion or about USD 700 million per year for a period of three years. This will assist the companies save considerable amount of commissions.

Russia and India to strengthen trade ties in gem and jewellery trade, By signing long term contracts, which include an agreement on direct supply of rough diamonds from Russia.

Business leaders from the two countries will sign contracts during the World Diamond Conference during President Vladimir Putin’s visit.

As the world’s largest manufacturing centre for cut and polished diamonds India produces 85 percent of the world’s polished supply, and Russia is the world’s largest miner of rough diamonds.

The diamond cutting and polishing factories in Namibia have been in decline, now employing only one thousand people.

The agreement between diamond producer De Beers and the Namibia Diamond Trading Company NDTC, which is equally owned by the two entities, currently supplies ten percent by value of all locally mined diamonds to the market.

The Namibian government is weighing up all options to provide more rough from (NDTC) to be supplied to the local cutting and polishing firms, said Minister Isak Katali.

International Court of Arbitration ruled in favour of the state owned diamond miner on Monday after previously ordering the seizure of about $45 million of rough diamonds.

The rough diamonds eventual ownership depends on a separate claim by fourteen Dutch farmers, who are seeking compensation for land seizures. The court also ruled that the diamonds belong to Zimbabwean mining companies, rather than the government. The court will hear the farmer’s case in December.

President Vladimir Putin is visiting India later this week. Hopes are high for the signing of a diamond supply agreement with Russian diamond mining giant Alrosa and India.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Putin will deliver speeches at the opening of the World Diamond Conference in New Delhi.

The speakers include De Beers Executive Director Stephen Lussier, Alrosa President Ilya Raschin and vice president Andrey Polyakov, Rio Tinto Diamonds CEO Jean Marc Lieberherr, and Endiama CEO Antonio Carlos Sumbula.

Government officials who will address at the event include Walter K. Chiadkwa, Minister of Mines and Mining Development of Zimbabwe, and Ngoako Ramatlhodi, Mining Minister of South Africa.

Consumers can now save thousands of dollars on diamonds, with a technological breakthrough that allows Synthetic diamonds to be created in a lab.

Bissell said the lab diamonds are not different in any material way and have all the optical, chemical and physical properties of mined diamonds, and they’re 100 percent carbon because they’re genuine diamonds.

The lab created diamonds are grown in pressurized containers on a small piece of carbon known as a seed,. The ultimate result is a high quality Synthetic diamond with the same properties as a natural diamond.

John King of the Gemmological Institute said lab grown diamonds are essentially the same as natural ones, and it’s just a matter of educating consumers.

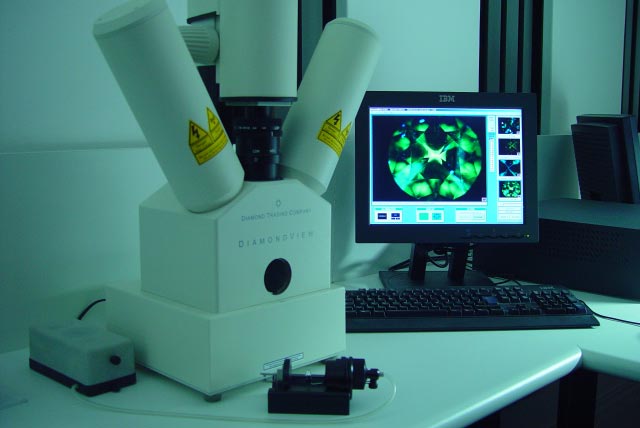

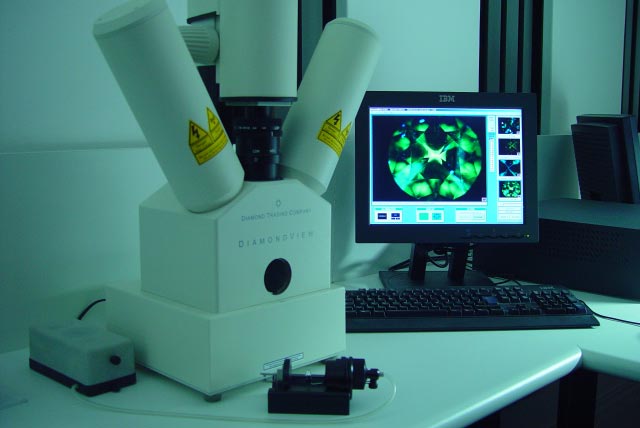

To keep up with the new technology equipment to test stones and prove natural or synthetic is available at laboratories.

Created diamonds do come with certification from some laboratories with regard to colour and clarity.

In Australia DCLA does not certificate treated or synthetic diamonds and guarantees all diamonds ever submitted have been tested and are natural as stated on the certificate.

NOTE: If you have a certificate or report which does not say the diamond is natural, it has NOT been tested.

The International Institute of Diamond Grading & Research is part of the

De Beers group of companies.

Based in Antwerp and run by the world’s top diamond experts, the International Institute of Diamond Grading & Research benefits from proprietary equipment of the De Beers group of companies that enables the most precise grading and assessment for both rough and polished diamonds

Read more